Operations at the long-standing Corentyne back track were abruptly shut down on Saturday after the Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA) issued cease-and-desist letters to all three operators – Golden Gloves Boat Services, Eno Bharat Boat Services, and KSN Boat Services – ordering an immediate halt to all incoming and outgoing vessel movements.

The closure, which took effect upon service of the letters, has placed approximately 25 workers directly employed by the operators on the breadline and disrupted the livelihoods of dozens of other service providers, including taxi drivers, porters, money changers, and food vendors who depend on the daily flow of passengers between Guyana and Suriname.

Copies of the letters obtained by this newspaper show that the GRA’s Law Enforcement and Investigation Division formally notified operators that Enos Landing, Corriverton, is not listed among the Authority’s approved ports of entry or sufferance wharves, and that no vessel is permitted to load or offload goods or baggage at the site unless directed by a proper Customs officer.

The correspondence states that the activities being conducted there are in direct contravention of the Customs Act, Chapter 82:01, and related regulations, and orders that all such unauthorised operations must cease with immediate effect. Operators were further warned that continued non-compliance could result in penalties and prosecution under the Act, and that the Commissioner of Police and the Director of the Customs Anti-Narcotic Unit had been informed of the matter and requested to provide support should the directive be ignored.

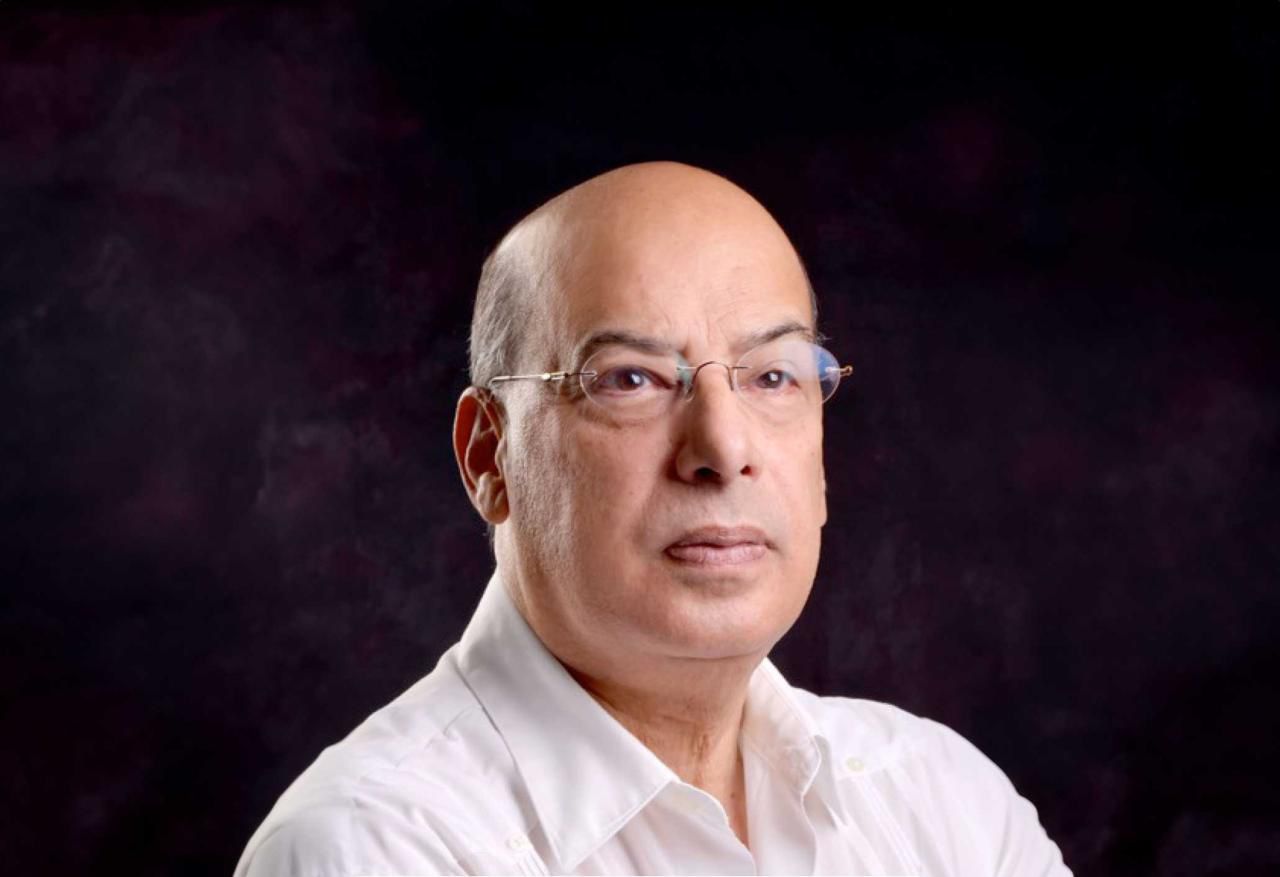

One of the affected operators, Mohamed Mursaleen, popularly known as “Golden Gloves,” said he was served the letter without any prior consultation or warning and was instructed that no passengers were to be transported.

“The customs officer called me, served me the letter, wanted me to sign it and told me that the operation is closed off for incoming vessel and outgoing vessel. Passengers are not allowed,” Mursaleen said.

While acknowledging the authority of the law, Mursaleen said the sudden closure has placed him and his workers in a state of uncertainty and financial distress. He explained that the back track has been in continuous operation for more than 75 years, spanning three generations of his family.

“This work has been going on from my grandparents to my parents and now to me. I have a lot of investment here, and they never give me a letter a month or two months before to let me prepare myself,” he said.

Mursaleen stated that his business alone employs more than 25 workers, all of whom depend solely on the operation for their income.

“Everybody includes all 25 employees. They have wives, they have children. This is the only work they have,” he said.

He added that his operation is not limited to transporting Surinamese passengers, but also serves business interests along the river.

“I normally carry Chinese contractors up the river to conduct business. This is not only for Surinamese people,” he explained.

According to Mursaleen, his company owns five boats, with three actively operating before the shutdown.

“I still got five boats, but three were working because you can’t keep them soaking all the time,” he said.

Addressing concerns about safety and regulation, Mursaleen insisted that his operation has always complied with marine and safety requirements.

“Every time the marine people come, they check for life jackets, and everything is up to date. We have the crew license, the boat license, and the captain’s name. We follow the rules,” he said.

He maintained that operators are willing to comply fully with Guyanese regulations once clear guidance and a reasonable timeline are provided.

“Whatever rules GRA wants, we are willing to comply with it,” he said.

On the issue of goods transported through the back track, Mursaleen said most items are small personal effects.

“When goods come in, it is like baggage duty goods — one bag or two bags. Most times, customs take the goods, and they go to the bank. We don’t even have storage here to keep goods,” he said.

Since the closure, economic activity in the Springlands area has slowed dramatically. Taxi drivers reported that they had not carried a single passenger to the landing all day on Saturday. Porters sat idly with their trolleys, while cambios closed early after business fell to almost nothing. Food vendors said prepared meals went unsold as foot traffic disappeared.

One porter, who has worked at the landing for over a decade, said he feared he would not be able to provide for his family if the closure continues.

“We live day to day. If the boats not running, we not eating,” he said.

Mursaleen recalled public remarks made by then President and now Vice President Bharrat Jagdeo in earlier years, when he indicated that once back-track operations complied with customs and regulatory requirements, there was no justification for shutting them down.

“He said once the back track operates according to customs and regulations, you have no reason to close it,” Mursaleen said.

Those statements, he said, gave operators confidence that regularisation, rather than elimination, was the intended direction of government policy.

Despite their frustration, operators say they are not interested in confrontation or protest.

“We don’t want to go to protests. We don’t want to jump the line. We want to work with the rules and regulations,” Mursaleen said.

He confirmed that arrangements are being made to meet with senior GRA official Roopnarine Singh early this week in an effort to resolve the matter.

“We are hoping to have a fruitful meeting so that we can receive cooperation,” he said.

He further stated that his business is fully open to inspection.

“You can check my place, my toilet, my department, my tax, everything is up to date,” he said.

The sudden closure has reignited a long-standing debate in Region Six about the balance between law enforcement and economic survival. While authorities argue that movement of passengers and goods outside approved ports of entry violates customs laws and creates security vulnerabilities, residents counter that the back track has long filled a practical transportation gap for traders, workers, and families.

For decades, the route has functioned as a daily artery of movement between Guyana and Suriname, forming an informal but deeply embedded part of life along the Corentyne Coast. Its closure has now replaced routine travel with uncertainty, anxiety, and fear.

As night fell on Saturday, boats remained tied at the landing, their engines silent. Workers sat in small groups, unsure when or whether operations would resume.

“This is not about boats only. This is about families,” one crew member said quietly.

Another added, “If this stays closed for long, plenty people going to suffer.”

For now, the Corentyne back track stands frozen in time, its future dependent on discussions between operators and authorities. Whether it will remain permanently closed or re-emerge under a regulated framework is yet to be determined.

But for the dozens of families who depended on it, the shutdown has already altered daily life, replacing certainty with struggle and long-standing routine with an uncertain wait. (Andrew Carmichael)

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Related News

Sir Ronald Sanders to be UG's new Chancellor

23 Greenwich families now hold legal title to their land

US$161M Soesdyke-Linden Highway upgrade now halfway mark